Revisiting the Gates Vascular Institute 10 years later

Danielle Larrabee

September 8, 2022

Social Sharing

One of the world's most innovative academic medical research buildings opened in the heart of Buffalo in 2012. What happened next?

The Kaleida Health Gates Vascular Institute (GVI) and the University at Buffalo Clinical Translational Research Center (CTRC) was a bold concept that hoped to create a first-of-its-kind translational healthcare environment where some of the greatest minds in vascular health could collaborate and innovate together in the heart of Buffalo’s medical campus. Ten years later, we asked—is the building achieving those original goals?

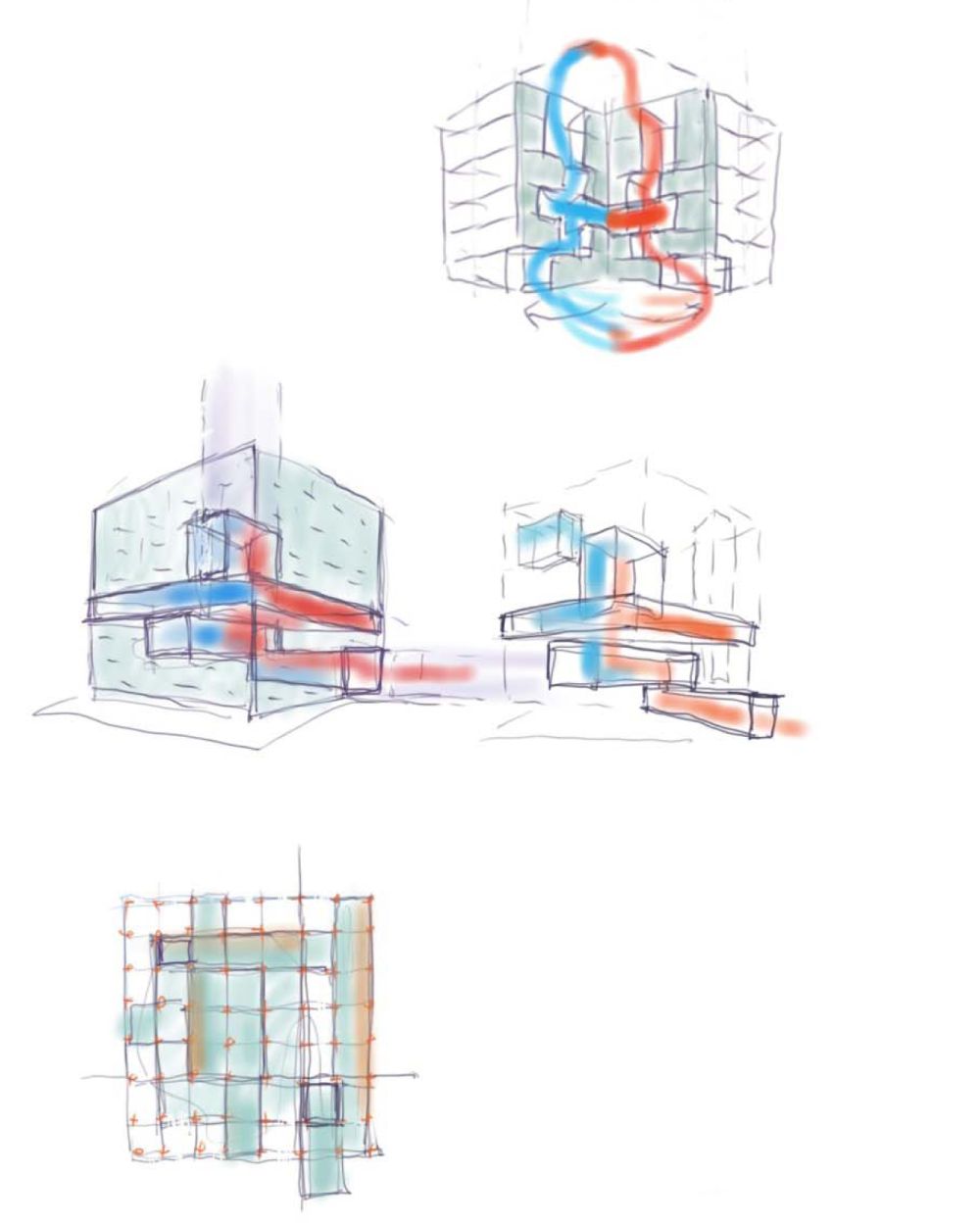

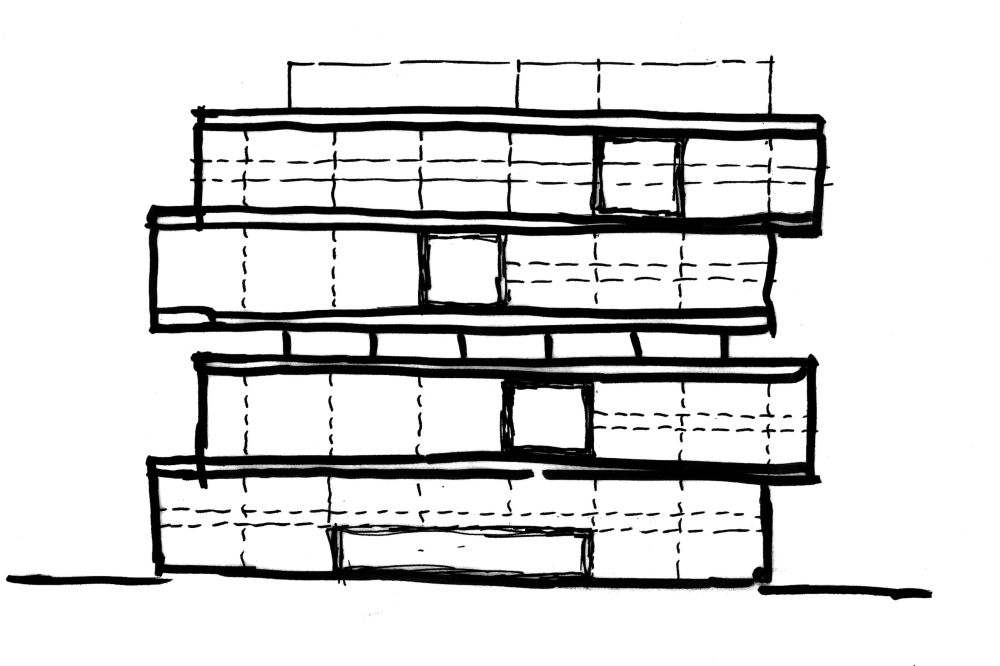

The strategy of the GVI/CTRC was to physically “stack” typically disparate departments—each with their own unique needs—to foster proximity between research and clinical practices. On the first four floors, the GVI operates as an internationally renowned clinical care facility and emergency department where physicians perform complicated procedures on patients needing stroke, cardiac and vascular care. On the top four floors, the CTRC houses scientists conducting cutting-edge research to improve health outcomes by preventing and treating a wide range of health conditions. Sandwiched between the two is the Jacobs Institute, an innovation accelerator focused on health and health technology, as well as a two-level collaborative core that unites all the unique disciplines together to move new discoveries from the bench to the bedside.

To understand the building’s impact over the past ten years, we interviewed various doctors and researchers to see if its original vision is alive and thriving.

The collaborative vision that started it all

Dr. Adnan Siddiqui, MD, PhD, FAHA, sat down to speak with us virtually after literally walking straight out of the OR, still donning his surgical cap and scrubs. Dr. Siddiqui is Vice Chairman and Professor of Neurosurgery at the State University of New York at Buffalo. He joined University at Buffalo (UB) Neurosurgery in 2007 and was part of some of the early conversations about the GVI/CTRC.

Both Kaleida Health and UB recognized increasing multidisciplinary collaboration and accelerating the bench-to-bedside cycle for medical breakthroughs would require a fundamental change in culture. There were many influential thought leaders on both the clinical and research side who worked together to bring the vision to life.

Dr. Siddiqui recalled some of the early meetings where CannonDesign was brought on to make this vision a reality. “I distinctly remember the CannonDesign team acted more like facilitators to the greater discussion happening,” he said. “Those early meetings were also where I met my colleagues in cardiology for the first time. Prior to those discussions, I would not have recognized them if I walked past them in the hallway. That collaborative spirit that began in your sessions lives on today in the building.”

A coffee chat leads to a world-changing procedure

For Dr. Siddiqui, he had many collaboration stories, but for him, one rose to the top. “There is a complicated brain blood vessel problem called arterial venous malformations,” he explained. “And there are some cases that cannot be treated through conventional means. I heard of a treatment where maybe you could stop the heart while you’re operating so the blood vessel would not bleed.”

“So, over a cup of coffee, I was discussing this method with Dr. Iyer, a cardiologist buddy of mine.” Dr. Iyer advised Siddiqui to stop the heart a certain way based on his experience of routinely stopping hearts when they replace valves in patients. Siddiqui was intrigued. “I asked him, ‘So, would you like to do this for me?’ On the next procedure, he came in and stopped the heart for me just like he described. We must have done 30 or 40 previously inoperable cases now with the cardiologists coming in to do their part and me doing my part.”

The doctors wrote a joint paper on this technique, and it is now how the rest of the world is starting to do this procedure—all of which began over a cup of coffee.

Today, Dr. Siddiqui interacts with his cardiology colleagues daily and collaborates with them on challenging vascular cases and vice versa with his neuro patients. “I’ll have someone having a heart attack on my table and I’ll call the cardiologists and they come in to treat it,” he said. “The same thing will happen during cardiovascular surgery. If their patient is having a stroke, I will come in and assist. We just take care of patients as complete people rather than having two separate admissions for neuro and cardio.”

He also finds himself up on the top floors interacting with the researchers quite often. That day when we spoke with him, he was on his way up to check on a new animal research study. “For me, it's back and forth, up and down the building all day long. I’m constantly collaborating with the researchers, writing new grants, working on new ideas for care and even inviting the graduate students to watch me operate."

Turbo-charging research and discovery

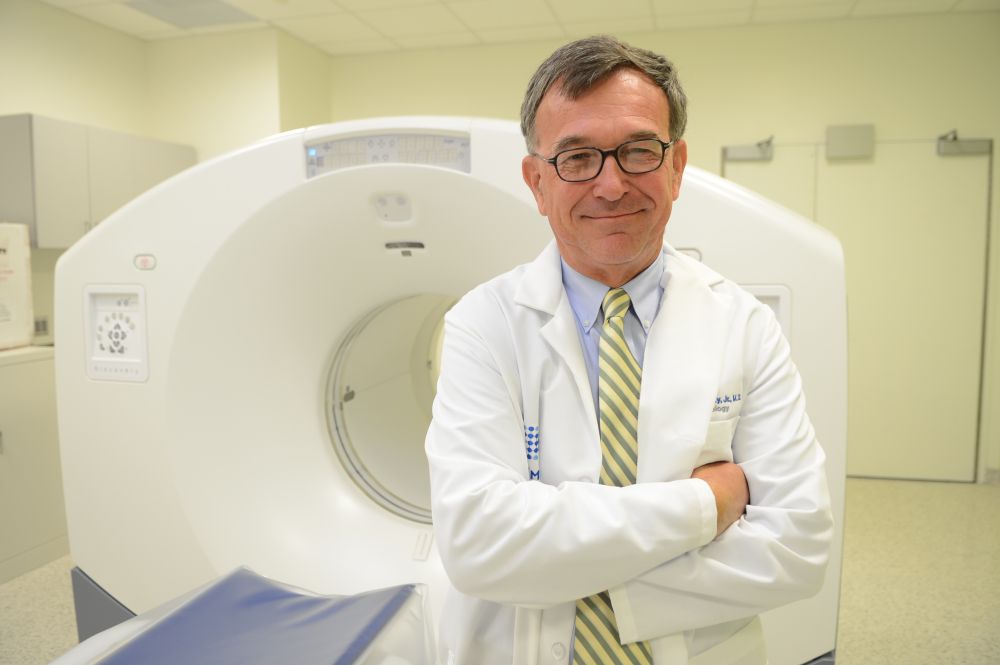

Moving up to those top floors of the building to the CTRC portion, on the sixth floor, we caught up with Dr. Timothy Murphy, MD, who is the director of the Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI)—the research organization that occupies the CTRC. Speaking with him over video conference, it is easy to see Dr. Murphy’s passion for his department, his colleagues and how the GVI/CTRC has helped propel translational research forward.

“Three years after the building opened in 2015, we received a very competitive, $15 million grant from the NIH,” Murphy said. “The Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) is awarded to only the top translational programs in the country. There is no doubt our building played a large role in receiving that grant along with the incredible collaboration from our researchers and clinicians who put in the work every day to facilitate translational research.”

Today, the CTSI spans the gamut of the full translational spectrum—where scientists perform “T0” basic research, including preclinical and animal studies all the way to the highest “T4” translation to communities including population-level outcomes research, monitoring of morbidity, mortality, benefits and risks, and impacts of policy and change. In 2020, the CTSI was again granted a second CTSA from the NIH for $21.7 million in recognition of Buffalo’s rapid upward trajectory in research and healthcare.

“My job is to be a facilitator, to interact with lots of different groups of people,” said Murphy. “This building enables me to do my job to the best of my ability.”

In 2020, the CTSI was again granted a second CTSA from the NIH for $21.7 million in recognition of Buffalo’s rapid upward trajectory in research and healthcare.

Unique elements

Dr. John Canty, MD, is Deputy Director at the CTSI and a SUNY Distinguished Professor involved in the clinical, teaching and research programs in the Division of Cardiovascular Medicine at UB. His research group conducts bench-to-bedside translational studies directed at advancing our understanding of cardiac pathophysiology, as well as developing new diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for the management of patients with chronic heart disease. When speaking with him, he reflected on the myriad and unique features of the building that set it apart from others globally.

“The design is so unique that each floor has its own characteristics, and are actually quite different, but they all work together as a whole entity,” said Canty. He was particularly proud of the Center for Biomedical Imaging (CBI) located on the seventh floor. The CBI provides infrastructure and advanced imaging expertise that is completely dedicated to research imaging.

The imaging facility is adjacent to the laboratory animal facility and the preclinical departments and basic research laboratories of the CTRC, which also houses the Clinical Research Center (CRC) on the 6th floor, which has a dedicated suite for clinical research. “Those types of adjacencies in one facility really don’t exist anywhere in the world,” said Canty.

Letting the light in

There were many trends we found when speaking with the doctors and researchers, but almost all of them commented on the ample natural daylight in the building. Many of them came from research spaces that were very compartmentalized and offered little in terms of daylight.

Dr. Murphy recalled his previous environment before he and his colleagues moved into the CTRC, “My department was in the middle of our previous building for 19 years and my lab had no windows,” he said. “You would go in in the morning and not see daylight until you left, if there was any left. It didn't bother me much when I was there, but after moving to the CTRC and experiencing the positive effects of so much natural light, it would bother me if it was taken away again.”

Dr. Murphy also described the skylight that spans three floors inside the atrium of the CTRC. “That skylight that was designed into the ceiling makes all the difference,” he said. “The light filters all the way from the seventh through to the fifth floor. I can see people mingling on the different floors. I can see researchers in their labs working. It’s so incredible how bright and open everything is.”

Translation in action

We asked everyone we interviewed how the proximity to each other has spurred innovation and collaboration across disciplines. Two stories stood out. One from Dr. Siddiqui and the final interviewee, Brian Weil, Ph.D., an Assistant Professor in the Department of Physiology and Biophysics.

Brian’s research is focused on the investigation of mechanisms underlying cardiac dysfunction and structural remodeling in heart disease, as well as novel therapeutic interventions to prevent or reverse left ventricular dysfunction caused by acute and chronic myocardial injury. In the second year in the building, in 2014, Brian and his colleague in cardiology performed a cross-disciplinary study where Brian worked directly with a cardiologist, Dr. Vijay Iyer, MD, from the GVI. Brain noted that Dr. Iyer would spend most of his time down in the GVI with his patients, but he also has an office located in the CTRC. They were studying and testing different medical heart pump devices that they would eventually use in patients in the GVI.

“We were performing our experiments up in the CRTC and Dr. Iyer would come up in between patients and see how we were progressing,” said Brian.

Additionally, when performing the studies upstairs, Brian could also use the expertise of the clinical doctors and nurses if he had a question about how a certain piece of equipment works in real-life clinical situations. Brian continued, “If something wasn’t working quite right, we’d ask, ‘do you have a second to come to look at something for us?’ To have that immediate access to the clinical side was critical to the success of that study and many others.”

Ten years later, still nothing else like it

It was apparent speaking with the doctors and researchers that they knew the GVI/CTRC was special in so many ways—from the unique spaces to the opportunities for collaboration to the ample natural light. Perhaps Dr. Siddiqui summed it up best …

“I am frequently traveling to major, advanced tertiary care medical centers all over the world. I have not had a single exception to the rule that I always feel incredibly proud of the place that I call home.”