Whole Child, Every Child: Pushing for equity in childhood

Maggie Bailey

November 23, 2023

Social Sharing

As designers of spaces and solutions for children and youth, we at CannonDesign are focused on the experiences of young people today. We’re always looking at ways to elevate their voices—and those of the myriad people who care for them—and exploring what more we can do to promote equity and inclusivity for future generations. This collection of efforts forms a design approach we call Whole Child, Every Child.

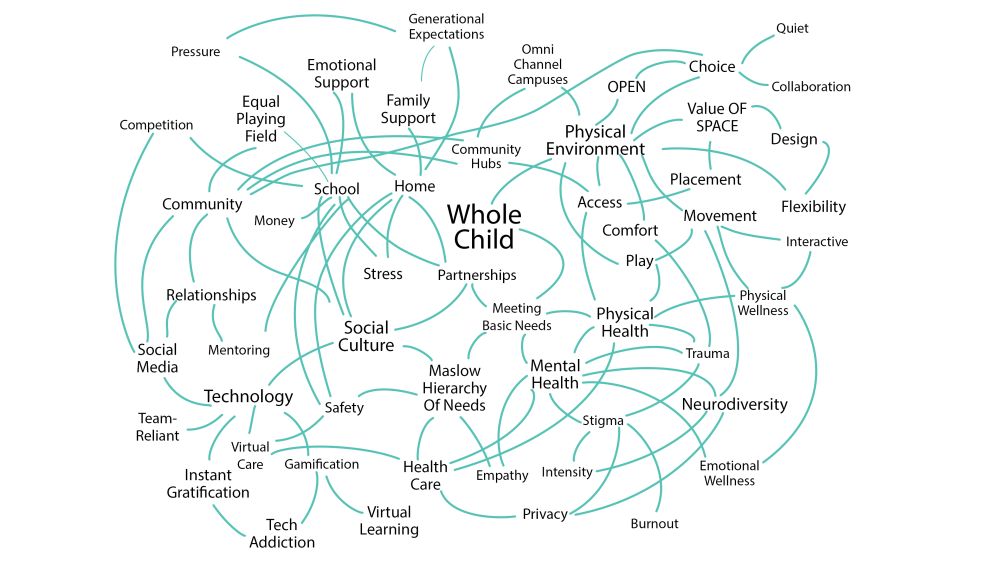

This approach stems from our Whole Child research initiative to uncover specific design elements that are most important to young people, families and their communities. What we found was a complex web of interdependencies that reflect young people’s unique needs.

Design considerations at different life stages

Designing spaces for children and youth must take into account their unique needs at different stages of their lives. “If we think about childhood development as a pyramid, what we consider as academic success might be at the pinnacle, but we also need the foundation of basic needs, social interaction, and mental and physical health,” says Marisa Nemcik, a student life strategist and designer in our education practice.

From preschool to elementary school, for example, considerations include durability and movement, as well as openness for play. But play is essential even in middle school, high school and higher education. “Play is universal, and it’s something we try to focus on infusing into our environments—that element of joy, wonder and whimsy,” says Kristie Alexander, our pediatric market strategist.

When children reach the age of eight or so, they start working on their social and emotional development, so a balance of group spaces with individual spaces for personal reflection and emotional control is key. When they transition into adolescence, they’ll need pre- and post-school support spaces, and as young adults in colleges and universities, the focus shifts to providing services that allow them to build the skills they need to become fully-fledged adults.

Throughout all these stages, Marisa highlights choice and flexibility as vital design considerations. “You’re designing for the point of choice and allowing young people to make decisions on where they want to be and how they want to interact, as well as creating spaces that allow them to play by the rules but also feel comfortable and engaged.”

Designing with mental health in mind

Our research initiative also found that mental health and physical spaces are inextricably intertwined. Now more than ever, preventative design strategies and trauma-informed design must be integrated into the environments where young people spend their time.

In the realm of trauma-informed design, “The goal is to reduce the number of triggers for people who have experienced trauma as they move through physical spaces,” says Stephanie Vito, one of our mental and behavioral health leaders. This includes designing more open spaces, ending corridors with daylight instead of darkness, ensuring multiple exit routes, and thinking about visual transparency.

When it comes to preventative design strategies, the idea is to ensure young people have access to the care they need to manage their mental health before a crisis occurs or escalates. This can be applied to everyday spaces in the community, such as places of respite in grocery stores, areas around shopping malls that allow connection to nature, and counseling services in pharmacies.

For higher education, preventative design strategies involve pairing physical health and mental health within the same space. “You’re providing visibility and access and making it more normalized,” Marisa says. “You’re bringing it in naturally and informing your mental health the same way you would go to the gym or go to a doctor’s appointment, and it becomes a healthy habit of equal importance.”

Creating more equitable and inclusive spaces

The feeling of belonging is crucial for children and young people, and our Whole Child, Every Child approach aims to use design to create more inclusive spaces, experiences and opportunities for them.

“It’s important to think of environments and spaces from as many perspectives and ranges as you possibly can,” says Kristie. She notes that pediatric healthcare institutions, for instance, are increasingly designing for a wide neurodiversity range—from neurotypical children to neuroatypical teens.

In education, one of the ways to foster a sense of belonging is to factor in the intersectionality of race, gender, culture, ability, identity and socioeconomic background, and provide spaces that reflect students authentically. “We call these affinity spaces, and we encourage students to make these spaces their own,” says Marisa. “When you feel safe and have this sense of belonging, you take more risks, which helps you grow. It’s because of that sense of community that allows you to try new things and make that leap.”

Overcoming the challenges of a Whole Child, Every Child approach

Addressing the broad spectrum of young people’s needs can be overwhelming and challenging, so we start with establishing common ground. “We find universal truths we can all agree on and let them be the beacon and guiding light as we move through design thinking,” says Paul Mills, our K-12 strategy leader.

Young people themselves need to have a voice and be involved in the design process. Paul saw this in action at the community forum he facilitated discussing Long Beach Unified School District’s Master Plan. “Typically, when I’m doing a master plan for a school district, I like to have students from that high school be part of the process because I’d like them to see the effects of their work and feel that they really made an impact,” he says. “I give them that agency to participate as a peer and they step up to it.”

Involving young people in the design process doesn’t have to entail something as wide-ranging as a school district’s master plan—it can include the smaller details such as involving them in decisions about public art, which we did at the CHOC Thompson Autism Center in Orange, California. “Our team did some research with children with autism and found that the kids were upset when they saw images of people who were alone,” Stephanie says. “Through that research, we realized that the images, silhouettes or graphics in the building should have multiple people in them to avoid the sense of loneliness perceived by the children.”

Most of all, we design with empathy at the forefront and try to see the world through a young person’s eyes. “Children have no agency over their own lives, so there’s a great responsibility that comes with designing spaces for them,” Kristie adds. “But it’s also really special to think about experiencing the world through the wonder of childhood. It’s the closest thing we have to magic, and it should be cherished, preserved and celebrated in whatever way we can.”